|

|

01 - Nisei Soldiers on the Pacific Front - "Summer of 1945"- Yoshiaki G. Takemura

Printed in The North American Post (Seattle, WA) on Dec. 8, 2010

Lasting three years and eight months, the Pacific War ended on August 15, 1945 with Japan’s unconditional surrender and acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. People throughout Japan and soldiers stationed outside the country alike all heard the Emperor’s radio broadcast declaring surrender.

About fifty years ago—from 1961 through 1965—I ministered a Buddhist temple in Ontario, Oregon, a town near the Idaho border. There was another Buddhist temple in Portland, on the western side of the state that counted Hiroshi Sunamoto as one of its active members. With a gentle manner, smiling face and above average height and physique, Hiroshi left a strong impression on me. The main character of this story, Satoru Tony Sunamoto, is his younger brother.

Tony Sunamoto was born in July 1915 in Port Blakely, Bainbridge Island, Washington. His father, Yozo Sunamoto, emigrated to Hawaii in June of 1904 from Koi, Hiroshima-ken and then came to Seattle six months later. Soon after, he moved to the outskirts of Portland, Ore., and worked on the farms for about six years. In 1910, he returned to Washington and started to cultivate strawberries on Bainbridge Island. His bride, Sen, arrived from Japan in 1911, and together they grew strawberries there for the next ten years. Blessed with the birth of three sons, in 1918 they decided to send their children to Japan to study and be taken care of by their grandparents in Hiroshima. Soon after, Yozo and Sen moved to Hillsboro, Oregon, and continued strawberry cultivation there.

Tony, who arrived in Japan with his old brothers Muneo and Hiroshi when he was three years old, enrolled in the local school near his grandparents’ house in Koi, Hiroshima-ken. After spending 13 years in Japan he quit middle school and returned to the United States with his brother Hiroshi. Tony was a typical Kibei Nisei who had just returned from Japan. He helped his father on the strawberry farm, but since he could not speak English he attended a local elementary school with students much younger than him in order to learn. He progressed quickly, becoming bilingual in only a few years and graduating from Banks High School in 1928. After graduation he continued to help out on his father’s strawberry farm along with his brother. They were busy in all phases of production: cultivating, shipping, marketing and maintenance and repair of farm equipment.

In December 1941, war broke out between the United States and Japan. Amidst severe racial discrimination and war hysteria, all persons of Japanese ancestry were driven out from the four western states’ specified military zones. In May of the following year the Sunamoto family was forced to abandon ripe strawberry fields ready for harvest in order to evacuate to the Portland Assembly Center where there was a county fair ground. After two months they were sent to the Minidoka Relocation Center near Hunt, Idaho.

Hiroshi, the eldest son in the family, did not come to Minidoka because he and his wife decided to grow sugar beets and potatoes in the outskirt of the eastern Oregon town of Ontario, which was outside of the military zone. Unable to decide on the free evacuation, the rest of the six Sunamoto family members settled in a roughly constructed barrack with tarred paper walls. More than 13,000 Nikkeis from the Portland and Seattle areas were housed at Minidoka, making it suddenly jump to being the eighth largest city in Idaho. Once their safety and livelihood were assured, the Sunamoto family gradually began adjusting to their new environment. However, to Tony the days felt tedious and long.

Volunteering military, being a MIS soldier

In January of 1943, the U.S. government decided to form a Nisei army unit and started to gather young volunteers in Hawaii and mainland relocation centers. At the relocation centers, they started conscripting from among those who answered “yes” to the question “If you were ordered to fight, would you do so no matter what the circumstances?” and sent them to Camp Shelby in Mississippi for training. The Nisei soldiers who had been in the army prior to the start of the war were either asked to leave the army or to move inland outside of the restricted areas. Along with the new recruits, the soldiers forced to move inland were also sent to Mississippi.

Tony enlisted in U.S. Army right after the loyalty questioning. For whatever reason, there were more volunteers from Minidoka Relocation Center than any of the other nine relocation centers. Soon after he arrived at Camp Shelby, he joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Company H as Pfc. (Private First Class) Sunamoto. After three to four months of training, most Nisei soldiers were sent to the Italian and French fronts to fight against Nazi Germany, becoming the now famous 442nd RCT.

Around the same time, a plan was being hatched to train Nisei soldiers for military intelligence in the Pacific Theater. Those who were fluent in Japanese were sent to Camp Savage in Minnesota to be trained as Military Intelligence Service (MIS), including Tony, who was transferred to Minnesota in July 1943. How torn Tony must have felt when he discovered that instead of going to Europe, he was to fight against Japan, the land of his ancestry and the country where he spent thirteen years of his boyhood.

He enrolled in Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) in July 1943 and began 30 weeks of intensive classes. Since he had no problem reading, writing from friendly fire (misidentification) as well as enemy fire. The reason why they were not allowed to carry rifles, machine guns or others must had resulted from the absence of and speaking Japanese, his progress was smooth and in the spring of 1944 he graduated from MISLS. At that time the U.S.’s counterattack was taking shape, so Tony was them the trust for the Nikkei on the part of US command. As a MIS soldier, his main duties were deciphering code, translating leaflets of psychological tactics and captured documents and interpreting prisoner questionings, although he also participated sent to the Pacific front and assigned to the Marine Corps as Technical Sergeant Sunamoto. I wonder how he felt on the front as Nikkei MIS soldiers were equipped only with grenades and knives in some army units. And they had their own bodyguards to protect in operations on the front line.

On the European Front, the Regimental Combat Team with its motto “Go for Broke” was well known by the American public, and its outstanding achievements were broadcast through newspapers, magazines, books and movies. On the other hand, the existence of the MIS soldiers known as “Yankee Samurai” was designated by President Harry Truman as “a secret weapon in this war” and kept in strict secrecy until the war’s end. However, their accomplishments were highly praised by General MacArthur’s headquarters that the Nisei’s contribution helped shorten the war in the Pacific by two years.

Delivering notice of surrender and disarmament

In August 1945, a garrison of 2,500 Japanese soldiers was stationed on the small island of Mili (part of the Marshall Islands in the Central Pacific) under the command of navy officer Captain Masanari Shiga. Even though the island was small (.9 by 1.3 miles), it had an airfield for Mitsubishi Zero fighters and bombers, and because it was one of the more strategically important Marshall Islands it was used as a base by the Japanese army. At the outset of the war 5,700 soldiers were stationed there, but that number decreased to less than half because of disease, hunger and repeated bombing by the U.S. military.

After conquering Majuro Island in February 1944 and securing the airport and anchorage area there, the United States changed to island hopping tactics and decided leave Mili without further attack—instead targeting Saipan Island and Iwo-jima Island, which were closer to the mainland Japan. When the war ended in August 1945, notice of surrender and disarmament was to be delivered to the unconquered islands where Japanese soldiers were still barricaded.

However, the navy was faced with the problem of selecting whom to send to Mili. Even though the war had ended, going to an island that had until yesterday been enemy territory would not be an easy task. Fully aware that it might lead to his death, Tony volunteered for this task and landed alone on this island that Japanese soldiers were determined to defend, bearing with him the mission of persuading the Japanese to surrender and disarm peacefully. The Japanese soldiers probably could not believe their eyes seeing a lone American soldier with a Japanese face.

As Mili Island was made of a coral reef formation, it was not suitable for crops other than a single product—coco nuts. In addition, because external supply lines (including to the mainland) had been cut off since the end of 1943, there was a severe lack of provisions leading to malnutrition and starvation. Upon this island on which even the snakes and frogs had long since disappeared, the soldiers were surviving on meager provisions and sheer force of will. Be that as it may, because of Japanese military’s “battlefield code” teaching soldiers “better to die than to be captured,” persuading them to accept peaceful surrender and disarmament would be no easy task. As conditions worsened for the Japanese army near the end of the Pacific War, it was not uncommon for soldiers who had exhausted every possible means fighting to decide to die together in one final assault. Tony wanted to avoid this.

With tears in his eyes, Tony appealed to Capt. Shiga with his own interpretation like “War is over, and there is no surrender or prisoner.” He spoke not just as one with same Japanese blood, but as man-to-man, samurai-to-samurai. Tony’s appeal of not wasting lives and of being able to send 2500 men back to their homes as quickly as possible moved the captain. When he heard “Yes” answer, it changed Tony’s tears to those of joy. The worst-case scenario of another round of hostilities safely evaded, and the Japanese flag was replaced with the Red Cross as both sides celebrated avoiding additional sacrifices. Being forced by a fateful war to fight against the country of his 13-year-childhood filled Tony with sorrow, but the fact that he was able to save the lives of those sharing the same blood gave him great happiness. He felt thankful that he had been elected as diplomatic envoy, since he was able to fulfill the desire of the American army to avoid unnecessary casualties for themselves, their allies and the Japanese. A few days after the Shiga-Sunamoto meeting, the American representative and Japanese army held a ceremony on Aug. 22 in which the surrender papers were officially signed, marking the first time the Japanese army signed a surrender treaty after the war.

Tony’s death and sword return to Japan

The Japanese army at Mili demobilized and the soldiers were repatriated, but Captain Shiga was sent to Majuro and charged with the crime of killing five American crew members who were captured in the ocean after trying to escape from their fallen plane. He was a graduate of Naval Academy in Etajima in Hiroshima, not far from where Tony grew up. Covering for his men, Shiga said, “I gave them an order. All responsibility lies in me, none in them.” And he killed himself like a samurai. Tony was heartbroken as he translated the captain’s words in the trial. At their last farewell, Shiga gave his most treasured sword to Tony, telling him to keep it. Thanks to his actions, the eleven subordinates who had undergone questioning along with him were able to return to Japan without further problems.

After being discharged from the army in January 1946, Tony married a Nisei woman Sueno (English name Jessie) and moved to Hawaii. He treasured the sword that Captain Shiga had given him and kept it at home. Tony felt a deep connection to Shiga, who had not only listened to his request for disarmament but covered up his subordinates’ action. Unfortunately, after the war ended Tony was struck with illness, and he passed away in June 1948, one month before his 33rd birthday, leaving his wife and nine-month-old daughter Shirley behind.

Before he died, Tony told his father that he wanted Shiga’s sword returned to his family. As swords are said to house a warrior’s soul, Tony’s father, Yozo, agreed with this request and after a long time spent searching for Shiga’s family, he arrived in Japan to return the sword to them. At the time, Shiga’s wife, Nobu, was working as a counselor at Wakayama Youth Authority and mother of five children. Yozo met Nobu and her middle-school-student son, Masanobu, at JTB (Japan Travel Bureau) Osaka head office and passed the sword on to Nobu, who gripped onto this memento of her husband tightly as it was finally returned to her.

Hero

This past October my aunt in Hillsboro, Oregon, passed away, and I attended the funeral at the Portland Buddhist Temple. After the funeral I unexpectedly ran into the second son of Hiroshi, Tony’s older brother. It was our first meeting, but when I asked him to tell me about his uncle, the first words out of his mouth were “He is a hero.” Hearing the same thing from him as from his father 50 years ago, my heart was filled yet again with the thought that Tony was indeed an amazing person. “My aunt died but Tony’s daughter is in Denver,” Hiroshi’s son said and gave me her name and telephone number. Someday, I hope that I am able to meet her.

This is a past and present story of an incident that happened 65 years ago in the summer of 1945 on a little island in the Pacific.

The end

Image Notes

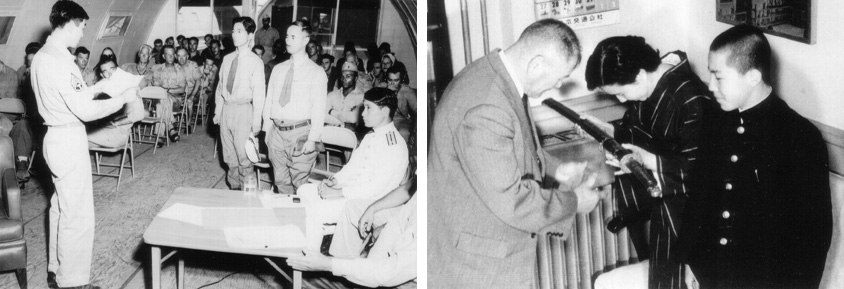

(Left): MIS soldier Tony Sunamoto, standing left, performing duties as trial translator on Mili Island after war's end. (Right): Yozo Sunamoto, father of Tony Sunamoto, returns Cap. Shiga’s sword to his family in Osaka. Photos provided by the Sunamoto family

Editor's Note

Yoshiaki G. Takemura displays collections of Japan-U.S. relations and Issei immigration at Issei Pioneer Museum in Hansville, Wash. More information about the museum can be found at (360) 638-1938, info@isseipioneermuseum.com or www.isseipioneermuseum.com.